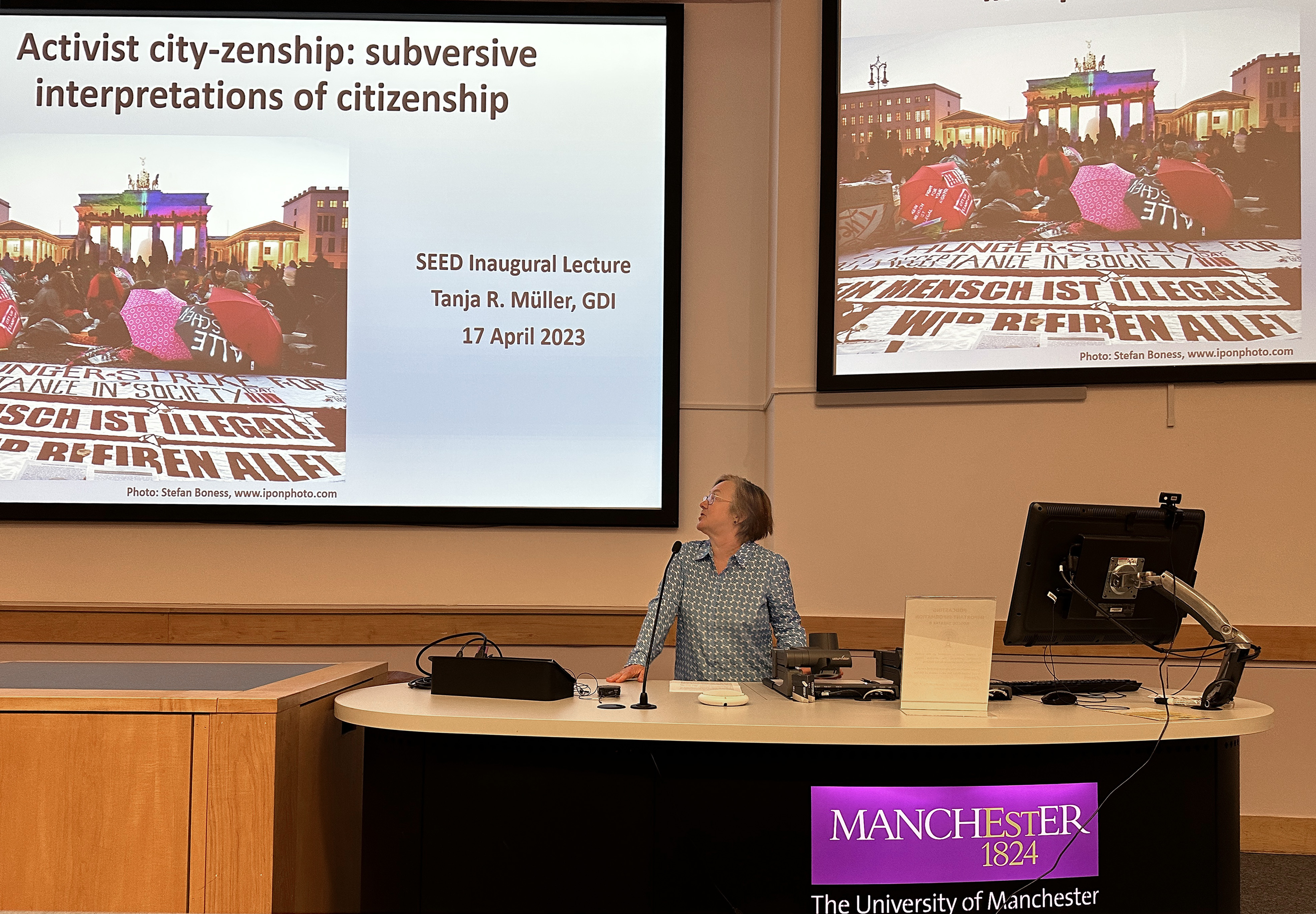

The recent occassion of a joint inaugural professorial lecture, postponed for three years during Covid-19, made me reflect on how my life as a woman in academia became intertwined with my intellectual curiosity.

In my political engagement long before academia, I grew up with the slogan, originally from the feminist movement, ‘the private is political’ – a slogan that in essence means one cannot or should not divide the private and the political, but even furtive acts of private resistance or solidarity have political repercussions, however small. The literature on activist citizenship has a similar argument at its core: It analyses acts by people who resist a status or a category they have been placed in, a category that usually denies them the rights they should have as human beings or in a specific geographical setting. Often, such acts involve solidarities across boundaries and population groups with different types of status and entitlements.

I came into academia late. I had a past as a political activist and a career as a journalist. Part of my past activism was around revolutionary movements, and I spent some time in Nicaragua in 1987, during the first Sandinista revolution. I had the privilege to live with a young woman who was active in the women’s movement in Nicaragua during that time, and encountered first hand an issue that has repeated itself over and over again in revolutionary movements: The aim to include women and transcend traditional gender norms, but at the same time remaining gender blind and often oppressive for women. The drive to get a clearer grasp on this made me do a PhD on elite women in the Eritrean revolution. I had worked as a journalist in Eritrea, and the best way to engage with this theme in depth was a PhD. The book top right is one of the outcomes.

I did not do the PhD to go into academia, but when the opportunity arose to take up an interesting position in an academic department, I found this worthwhile exploring and started my life as a perofessional academic in January 2006.

While I had worked on the struggles of women before, I never felt disadvantaged as a woman – until I joined a university department. One of my first memorable encounters was a senior male colleague wanting to have coffee, and it soon turned out they simply wanted to see if my knowledge of Ethiopia would be beneficial to them. As soon as they realised I was working on Eritrea, in fact a different country, they lost interest and ended the encounter rather abruptly. Why do I mention this? Because encounters like this set the tone. If I had been a young academic whose main aim in life was an academic career, I would have been devastated by this and many subsequent encounters that followed a similar script, and the structures underpinning such encounters. I shrugged it off because I had a previous successful career, and saw academia as something to try to see if it worked for me.

I have over the years seen too many women colleagues crushed by dynamics like this – some have left academic for good even though they would have made valuable contributions, other only left their university. While these days a lot of equality, diversity and inclusion initiatives and procedures are in place, it is these hidden dynamics and structures that are so toxic, and that are not easily brought into the open, complained about, raised – and that makes working in many academic departments to this day so much easier if one is white, male, and has a grande sense of entitlement. I want to dedicate this blog to those of my women colleagues who left or felt they were forced to leave, and whose intellectual input is still missed and has made many university departments including my own arguably a poorer place – but also the batch of newish women colleagues, some of whom I have or had the privilege to mentor: I hope you will find an easier path to fulfilling careers than my generation.

I am a survivor of those dynamics – and there have been many more often painful examples, also very recently and in particular during COVID, examples of mansplaining or indirect discrimination. I am a survivor partly because of my previous biography, but also because I was lucky in many ways. And I owe me still being in academia to some great colleagues, colleagues who always believed in me and supported me. They know who they are and I am truly humbled and greatful for you being here.

You must be logged in to post a comment.