It has become a common trope to describe the current movement of people towards safety in Europe or other places as the biggest such movement since WW II. It thus seems pertinent to remember one of the poignant journeys of that time, the flight of German philosopher Walter Benjamin across the Pyrenees from France to Spain in 1940 that ended with Benjamin’s death.

It has become a common trope to describe the current movement of people towards safety in Europe or other places as the biggest such movement since WW II. It thus seems pertinent to remember one of the poignant journeys of that time, the flight of German philosopher Walter Benjamin across the Pyrenees from France to Spain in 1940 that ended with Benjamin’s death.

What is now a hiking trail, 17 kilometres in length and with 600 metres difference in altitude to overcome, was then one of the last passages to freedom – or so Benjamin hoped.  Born in Berlin in 1892, philosopher, writer, Jew, and communist sympathizer, Benjamin first had to leave in 1933 when the Nazis came to power and went into exile to Paris. But by 1940 Paris was de-facto under Nazi occupation and not a safe place any longer.

Born in Berlin in 1892, philosopher, writer, Jew, and communist sympathizer, Benjamin first had to leave in 1933 when the Nazis came to power and went into exile to Paris. But by 1940 Paris was de-facto under Nazi occupation and not a safe place any longer.

Benjamin thus travelled to Banyuls-sur-Mer, on the French border with Spain, from where one could reach Portbou on the Spanish side.  Even though Spain was ruled by the Spanish version of fascism under Franco, it was still possible to obtain a visa to the USA there. And that was Benjamin’s plan: to travel from Portbou first to Lisbon and then board a ship to the USA and to freedom, finally. He was to travel on paths used by local smugglers but also by Spanish republican fighters and international brigades in the Spanish civil war – who had fled from Spain to France in the opposite direction.

Even though Spain was ruled by the Spanish version of fascism under Franco, it was still possible to obtain a visa to the USA there. And that was Benjamin’s plan: to travel from Portbou first to Lisbon and then board a ship to the USA and to freedom, finally. He was to travel on paths used by local smugglers but also by Spanish republican fighters and international brigades in the Spanish civil war – who had fled from Spain to France in the opposite direction.

The ‘people smugglers’ at the time were people like Lisa and Hans Fittko, both refugees from the Nazis themselves, who then lived in Banyuls and helped others in need to make it to Spain.  Benjamin and his small group were in fact the first refugees guided by Lisa. She hard warned him, the track was dangerous and exhausting, but there was no other option. In fact it must have felt like torture to Benjamin, who was suffering from a heart condition as well as breathing problems.

Benjamin and his small group were in fact the first refugees guided by Lisa. She hard warned him, the track was dangerous and exhausting, but there was no other option. In fact it must have felt like torture to Benjamin, who was suffering from a heart condition as well as breathing problems.  On top of that he was carrying a heavy dispatch case full of manuscript papers and other documents that he would not let go off. When it became clear Benjamin would not manage the track in one day, Lisa and the group left him to rest over night and returned the next day to continue a track that takes a normally fit person a mere six hours.

On top of that he was carrying a heavy dispatch case full of manuscript papers and other documents that he would not let go off. When it became clear Benjamin would not manage the track in one day, Lisa and the group left him to rest over night and returned the next day to continue a track that takes a normally fit person a mere six hours.

Benjamin and his fellow refugees eventually made it to Portbou – Lisa had to leave them on top of the mountain at the Spanish border as it was too dangerous for her to cross, but from there it was straight down to the blue Mediterranean sea. Because Benjamin and his group did not have an exit stamp from the French side, however, Spanish border guards put them into a small hotel but threatened to send them back to France the next day.

Because Benjamin and his group did not have an exit stamp from the French side, however, Spanish border guards put them into a small hotel but threatened to send them back to France the next day.  With hindsight it is not clear whether this was a real threat or simply an attempt at blackmailing. Benjamin took the threat seriously and poisoned himself during the night. Attempts to safe his life were unsuccessful and he died on 27 September 1940. Those who travelled with him were subsequently allowed to continue their journey – thus one could say his sacrifice became their salvation.

With hindsight it is not clear whether this was a real threat or simply an attempt at blackmailing. Benjamin took the threat seriously and poisoned himself during the night. Attempts to safe his life were unsuccessful and he died on 27 September 1940. Those who travelled with him were subsequently allowed to continue their journey – thus one could say his sacrifice became their salvation.

This route of the last journey of Walter Benjamin has been opened in 2009 as a cross-border walking trail, the Chemin Walter Benjamin on the French, and Ruta Walter Benjamin on the Spanish side, but the name is were similarities end. It starts at the Hotel de Ville in Banyuls and in theory the tourist information point opposite provides those interested with a map. A look at that map makes one gasp: It ends on top of the mountain at the border with Spain with a vague arrow pointing towards the direction of Portbou.

When questioning this slightly bizarre fact, staff at the tourist office reply with some incredulity mais, c’est l’Espagne as if referring to a somehow dangerous and far-away place, not to a neighbouring country in supposedly border-free Schengen-Europe. Luckily, once arrived at that border, it becomes clear that the Spanish side takes the memorialisation of Benjamin’s last journey much more seriously.

When questioning this slightly bizarre fact, staff at the tourist office reply with some incredulity mais, c’est l’Espagne as if referring to a somehow dangerous and far-away place, not to a neighbouring country in supposedly border-free Schengen-Europe. Luckily, once arrived at that border, it becomes clear that the Spanish side takes the memorialisation of Benjamin’s last journey much more seriously.  While on the French side few arrows and other markers far and wide point the way and one can actually get lost, the Spanish part of the trail is not only clearly marked but also provides a lot of additional information on extensive information tableaus. Whether this may be the case because Benjamin actually fled France and sought his freedom on route to Spain, or because the French fail to acknowledge anybody as a great philosopher who is not actually French, remains a puzzle.

While on the French side few arrows and other markers far and wide point the way and one can actually get lost, the Spanish part of the trail is not only clearly marked but also provides a lot of additional information on extensive information tableaus. Whether this may be the case because Benjamin actually fled France and sought his freedom on route to Spain, or because the French fail to acknowledge anybody as a great philosopher who is not actually French, remains a puzzle.

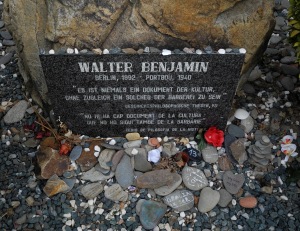

Shortly before Portbou, one walks past an old façade with a faded graffiti that reads ‘sortie’, curiously in French.  It strikes one as almost cynical when imagining how Benjamin must have felt had he seen the graffiti – if indeed it was already there at the time of his passage. In Portbou itself the trail of today’s wanderer can be brought to an end in two different ways: The first is a visit to Benjamin’s grave in the local cemetery. The second is a visit to the monument erected in 1994 by Israeli artist Dani Caravan in order to celebrate Benjamin’s memory.

It strikes one as almost cynical when imagining how Benjamin must have felt had he seen the graffiti – if indeed it was already there at the time of his passage. In Portbou itself the trail of today’s wanderer can be brought to an end in two different ways: The first is a visit to Benjamin’s grave in the local cemetery. The second is a visit to the monument erected in 1994 by Israeli artist Dani Caravan in order to celebrate Benjamin’s memory.  Not far from the cemetery, it consists of a walled-in iron staircase that ends high above the sea with a glass wall. Walking the staircase to the end allows a view to the far horizon, and invites the visitor to imagine freedoms and dreams of any kind. But one cannot pass through the glass, so the only route forwards is to turn back. The installation is called passages – and is a fitting memorial to the memory of a great philosopher whose life was cut short by a brutal political regime, and whose last manuscript was almost carried to freedom but has since been lost.

Not far from the cemetery, it consists of a walled-in iron staircase that ends high above the sea with a glass wall. Walking the staircase to the end allows a view to the far horizon, and invites the visitor to imagine freedoms and dreams of any kind. But one cannot pass through the glass, so the only route forwards is to turn back. The installation is called passages – and is a fitting memorial to the memory of a great philosopher whose life was cut short by a brutal political regime, and whose last manuscript was almost carried to freedom but has since been lost.

It also makes one think about the many lives lost on our shores in 2015, many anonymous and some in the limelight.  I thus wish to dedicate my walk tracing Benjamin’s journey to all of them – to their different hopes and aspirations. May they eventually receive the hospitality that was denied to Benjamin, and may we, the citizens of Europe, not forget the values that are at the core of the European project: freedom, security and justice without internal frontiers. Each new fence that is being erected at any European border, each train station or port that is being blocked to those without proper papers, and each asylum accommodation that goes up in flames, are betraying not only European ideals but also those who seek sanctuary. Those who like Benjamin 75 years ago longed for freedom.

I thus wish to dedicate my walk tracing Benjamin’s journey to all of them – to their different hopes and aspirations. May they eventually receive the hospitality that was denied to Benjamin, and may we, the citizens of Europe, not forget the values that are at the core of the European project: freedom, security and justice without internal frontiers. Each new fence that is being erected at any European border, each train station or port that is being blocked to those without proper papers, and each asylum accommodation that goes up in flames, are betraying not only European ideals but also those who seek sanctuary. Those who like Benjamin 75 years ago longed for freedom.

Lisa Fittko has written a memoir of the journeys she facilitated across the Pyrenees, see: Lisa Fittko, Escape through the Pyrenees, 2000, Northwestern University Press.

Pingback: Flight to the end of the road not a passage to freedom: in memory of Walter Benjamin - Manchester CallingManchester Calling